"davesaddiction @ opposite-lock.com" (davesaddiction)

"davesaddiction @ opposite-lock.com" (davesaddiction)

03/14/2019 at 10:42 • Filed to: None

3

3

0

0

"davesaddiction @ opposite-lock.com" (davesaddiction)

"davesaddiction @ opposite-lock.com" (davesaddiction)

03/14/2019 at 10:42 • Filed to: None |  3 3

|  0 0 |

Sam Posey is 72 years old and as colorful as ever. As if to prove it, when we catch up with the race-car driver, Formula 1 commentator, and author of “The Mudge Pond Express,” one of the 1970s most-gripping racing autobiographies, he’s padding around his studio in Sharon, Connecticut, with an easel and a multihued array of oil paints at the ready. At the opposite end of the high-ceiling barn-cum-studio — designed, like everything else on the property, by Posey, who did the landscaping as well — we see where his wife, artist Ellen Griesedieck, has been assembling the American Mural Project, a 3D collaboration of artists from around the country she’s directing that honors the American worker. When unveiled later this year, expect it to be the world’s largest piece of interactive indoor artwork, spanning 125 feet wide and 30 feet tall.

Posey beams with pride describing his wife’s work but apologizes for his speech. He worries he may be difficult to understand on account of the Parkinson’s disease he was diagnosed with 22 years ago and which has worsened over time. But Posey remains easy to follow and — better still — well worth following. Energetic and youthful in appearance, with trademark eyebrows that look like they have their own electric power supply, he’s an effervescent archetype, a midcentury Yankee Renaissance man. A uniquely American character, Posey’s journey from Connecticut country homes and elite New York City private schools to an eclectic and industrious life spent racing, writing, broadcasting, designing buildings, and painting can’t be replicated.

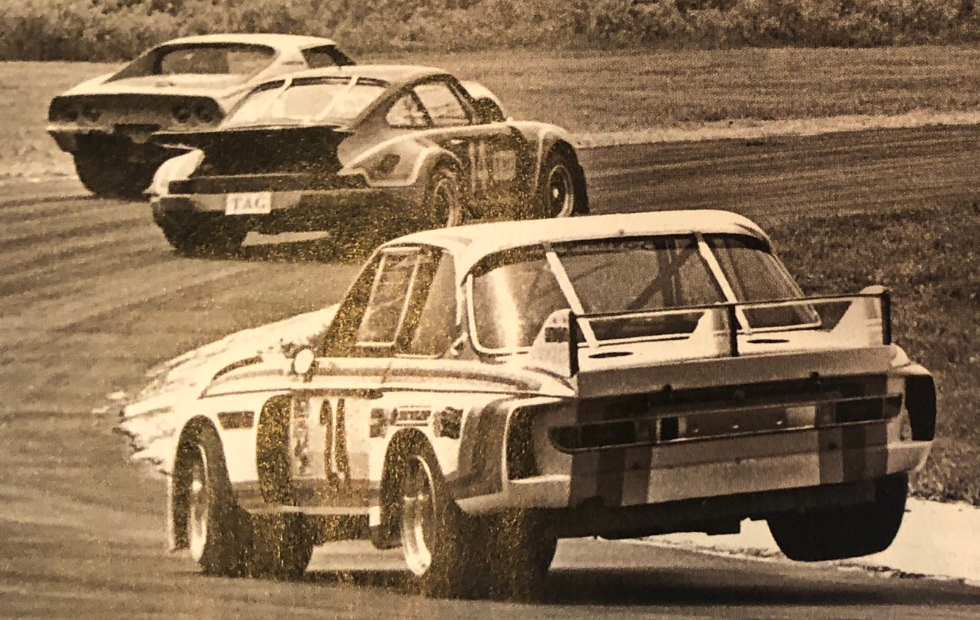

Looking back at it all, Posey observes with genuine surprise and bemusement: “It’s just, things keep coming out right when I do them.” Known on air and off for economical, insightful prose — sometimes upbeat, sometimes elegiac — Posey stands out among racing commentators. He’s wry, thoughtful, and particularly well-informed. The subject is something he knows quite a bit about, having been a driver of some note in the day when competition was as long on excitement and glamour as it was on danger. His years on the track (1965-1982) coincided with the closing hours of racing’s free-for-all period, a less-regulated time that some see as the sport’s most interesting era, though also among its most dangerous with a depressingly high fatality rate. Driving in all manner of cars, series, and formulas, Posey often placed and sometimes won, with stops in Formula Vee, Indianapolis, Le Mans, Can-Am, Formula 5000, Tasman, Champ Car, NASCAR, Trans-Am, and F1 with cars as diverse and brutishly powerful as the Surtees TS9B, Ferrari 312M, and Dodge Challenger as well as McLarens, Bizzarinis. Even the Caldwell, a car devised by engineer Ray Caldwell and his designer, driver, and chief financial backer, our host, Sam Posey.

Born to a well-to-do family that split its time between Manhattan’s Upper East Side and old money, Brahman northern Connecticut, Posey spent all of one day with his father before he went off to war in 1944. His father would later lose his life to a kamikaze in Okinawa. But Sam was young, and he had a mother, Mary, who doted on her son and enthusiastically supported his youthful fixation on competition and speed. In 1958 when he was 14, she agreed to buy him a 2-year-old Mercedes-Benz 300 SL Gullwing from a charter member of post-war Connecticut’s elite international racing fraternity, the racer and sometime car dealer John Fitch, for the princely sum of $2,500. In this silver machine, which Posey still owns, he taught himself to drive fast, garnering car-control basics by whipping through rural fields of alfalfa and setting the stage for a victorious run up Vermont’s Mount Equinox hill climb. “It turned out it was an absolutely perfect car for the thing because you turned in, and the rear suspension jacked, you’d floor it, and basically it would slide out behind, the axles would come back, and then you’d have a straight shot,” he says. A Formula Vee car sharpened his skills further.

“It was remarkable to me that she would let me do this,” Posey admits of his mother. “But she always said it was the only thing I was good at. I was terrible in school. Bottom of the class all the time, just couldn’t do math, couldn’t do languages. English was fine. I was in good shape there...

Thanks to T. Donohue for pointing me down this rabbit hole - read the rest here:

!!! UNKNOWN CONTENT TYPE !!!